By Fiona Graham

Technology of business reporter, Nairobi and Kampala

WATCH: In Kenya, only the very richest are guaranteed quality healthcare. The BBC’s Fiona Graham looks at the technology that could change that

“I had just attended too many funerals, people dying from completely preventable causes and treatable diseases.

“Standing at the sides of the graves and holding the babies of parents who had died from basic infections that are treatable in other parts of the world.” Stephanie Koczela is one of the founders of Penda Health, and she’s explaining what motivated her and her colleagues to open their first clinic in the town of Kitengela.

It’s a huge, sprawling, dusty conurbation that’s growing explosively, absorbing the overflow of people from nearby Nairobi.

A trip to the doctor’s in much of East Africa can be something of a game of Russian roulette.

As co-founder Beatrice Ongoce puts it: “In Kenya, healthcare quality is associated with being rich, being able to pay more, and bad options are related to being poor.”

Stephanie Koczela and Beatrice Ongoce at the Penda Health Clinic

The start-up aims to provide quality, affordable healthcare for the middle and lower income segments of Kenyan society. And to do this technology plays a big part.

“The surprising thing is that middle 70%, they spend about $1bn a year on outpatient healthcare alone in Kenya,” according to the third part of the team, Nicholas Sowden.

Lock, stock

This means there’s plenty of incentive to find ways to cut costs while keeping standards high.

“I think that most of the health care providers that we’re competing with don’t use technology at all to supplement their systems,” says Ms Koczela.

“They’re all paper records, their drugs are often out of stock.

Kitengela lies next to the Nairobi National Park, and is growing fast, as its neighbour Nairobi continues to expand

“We have a system that gives us a warning if any of our drugs are expired, and it forces our providers to dispose of those drugs immediately.”

Penda Health’s system is bespoke, tracking stock and expiry dates through a simple interface accessible from a PC. When supplies run low, this triggers a warning to make sure more is ordered.

“It raises our medical quality. One of the most common problems with healthcare providers in Kenya is that they don’t have the equipment that’s necessary to provide medical care.

The start-up had originally focused on women’s healthcare, including family planning and reproductive health, but soon realised that to attract women you need to treat the whole family

“This system ensures that we will always have what’s necessary for our patients.”

The clinic uses mobile broadband, meaning the system is completely portable – and mobile technology is useful in other ways.

Staff text patients to make sure they’re taking their drugs at the right times and in the right way, or to tell groups of patients that a specialist is visiting. Investing in an internet connection means accessing online resources to build up-to-date treatment protocols is fairly straightforward.

The start-up is now working on developing their own electronic medical records system – that ultimately will allow them to share those records if need be with specialists both within Kenya and internationally.

“We want to be the most friendly and highest quality provider for the low and middle-income Kenyan, and in order to do that we need to have tech systems that are backing our chain,” says Ms Koczela.

Right of way

For some Kenyans even the most basic clinic can seem out of reach. For many people living in rural areas, the nearest hospital could be many days’ journey away. Living in a rural area can mean that a trip to a doctor could take days. If you need to see a specialist, this means a referral, another long journey and probably a lengthy wait.

So to tackle this Amref – the African Medical and Research Foundation – is using computers and the internet to let local healthcare professionals consult urban experts.

The next step is to build an online knowledge base, says Amref’s Frank Odhiambo

“This technology is important because it helps cover the great distance that the poor have to cover while seeking healthcare,” says Frank Odhiambo, Amref’s telemedicine project officer.

The telemedicine equipment – computers, printers, scanners, and digital cameras – is provided by Computer Aid International.

The technology has been installed in around 50 hospitals in Kenya, as well as in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Uganda, with more planned.

Operating in rural areas means connectivity is one of the project’s biggest challenges.

Although fibre-optic cable is gradually being rolled out through the region, large areas are still reliant on 2G mobile broadband, and even satellite broadband, which is pricey.

The telemedicine technology lets rural doctors share pictures and x-rays with specialists to find the right diagnosis. A reliable electricity supply is the other conundrum in rural areas. So Computer Aid is supplying Amref with solar-powered Zuba boxes – shipping containers fitted out as cyber cafes.

For Mr Odhiambo, the rewards of the project are clear.

“What I find most rewarding is availing a solution to someone in the most remote location, who does not have hope. IT just does it like magic.”

Beat of your heart

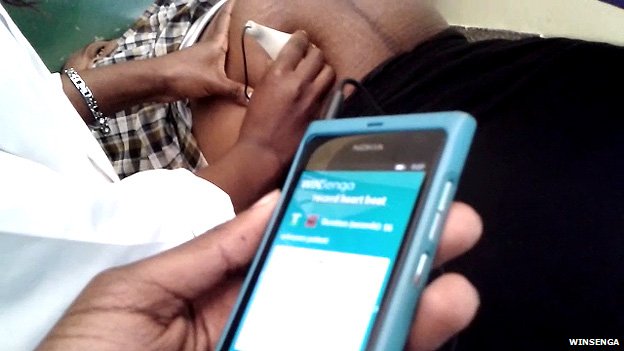

The mobile phone in your pocket can also prove an effective way to give people in isolated areas access to healthcare technology.

“Africa has a high mobile penetration rate,” says Aaron Tsushabe, an app developer with Uganda start-up ThinVoid.

The team behind WinSenga got the idea for the app after watching a nurse using a pinard horn . “They actually say that in about three years’ time there will be more phones in Africa than in the US.”

Mr Tsushabe and his team – all students at Makere University in Kampala – have developed an app that matches smartphone technology with the pinard horn, which has been in use for over 100 years to monitor the heart rate of unborn babies.

Joseph Kaizzi and Aaron Tsushabe have renamed the adapted pinard horn the senga horn

It resembles an old-fashioned ear horn, and is used by placing the wide end of the cone on the abdomen of a pregnant woman, and listening.

You then count the beats to calculate the fetal heartrate – one of the primary indicators of the health of the child.

This simple piece of technology is still widely used in developing countries.

The students took the pinard horn, and fitted it with a microphone, which plugs into the phone. The app monitors the sound of the baby’s heart, and can then indicate if there is any cause for concern.

The team recently took part in Microsoft’s Imagine Cup, the student technology competition, placing in the top 20 globally.

WinSenga is still in the prototype stage, although ThinVoid’s Joseph Kaizzi says they hope that it will be available generally very soon.

WinSenga takes smartphone technology and matches it with a pinard horn, a device invented in the 19th century by a French obstetrician, Dr Adolphe Pinard

“We’re working hard with the consultant from Unicef trying to make this as adaptable as possible, and we’re trying to localise it.

“It’s currently in English, we’re trying to get it in some of our local dialects.”

Dr Felix Olale is executive chairman at investment banking firm Excelsior Firm, based in Nairobi. He is also an adviser to the Kenyan government.

He says the future for healthcare in the regions depends heavily on investment in technology innovation.

“Ultimately it’s about patients and outcomes.

“It’s about increasing access to care for these folks who may not have access to facilities. It’s about increasing the socio-economic growth of these communities. Technology allows you to do all these things, right?

Dr Felix Olale: The future for healthcare in rural areas depends on investment in technology

“If we can take technology and build off of the infrastructure that’s already in place, what that does, it allows us to push these at a low investment for the amount of return that you actually get.”

In Kitengela, Penda Health has taken its reliance on technology one step further, issuing what they call “social shares” to fund their first clinic.

They used social media platform Facebook to find investors prepared to lend them the money to pay for the bricks, mortar and equipment needed.

They have big ambitions – and those ambitions rely heavily on technology to push growth.

“Technology allows us to have quality healthcare at scale,” says Penda Health’s Stephanie Koczela.

“With one clinic you could imagine we could monitor our drug supplies and do chart review with paper and all those things.

“But with a hundred clinics that’s just not possible. The only way to do that is to leverage amazing systems.”

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-18969646