By: Primah Kwagala

A pregnant woman went to Uganda’s largest hospital to deliver her baby. After her labor stalled, she was wheeled to the operating room, where her newborn was delivered by caesarean section. When the woman awoke from surgery, her baby was gone. No one at the hospital would tell her what happened to her child.

A pregnant woman went to Uganda’s largest hospital to deliver her baby. After her labor stalled, she was wheeled to the operating room, where her newborn was delivered by caesarean section. When the woman awoke from surgery, her baby was gone. No one at the hospital would tell her what happened to her child.

Another woman went to the same hospital to deliver twins. When she woke from surgery, she was handed one baby instead of two. The hospital said the twin had died, but there was no explanation of what went wrong and no body to bury. Months later, the hospital turned over a body, but DNA testing proved it did not belong to the grieving parents.

No mother should have to experience the pain of losing a child. When the hospital cannot explain what happened or even hand over a body for burial, it is a clear violation of the constitutional right to health. Uganda’s High Court agreed in a January 2017 ruling. So why hasn’t the hospital fully complied with the court’s order that it change its policies to ensure this doesn’t happen again?

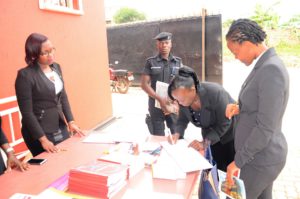

As a human rights lawyer, I hear heartbreaking cases like this all too often. Our clients deserve justice. It is not enough for us to win these cases in court. We want proof that the hospital is taking steps to protect these precious lives.

We rejoiced last year when Lady Justice Lydia Mugambe ruled that Mulago National Referral Hospital had violated the parents’ right to health and freedom from torture when it failed to produce their baby’s body.

“The plaintiffs were denied an opportunity to carry out burial rituals for their child, which in my view would have constituted a fundamental part of their healing process,” Justice Mugambe said in her decision. “By denying them the opportunity to bury their baby, the defendants compounded their pain and subjected them to more psychological torture.”

It has been more than a year since the court handed down its ruling, which included financial damages to the bereaved couple and required that the hospital take steps to safeguard babies. We have received no report from the police, hospital or government on any progress toward improving hospital procedures.

We are seeking some simple, inexpensive fixes. Place surveillance cameras in the maternity wing to monitor the movement of babies. Hold midwives accountable when babies in their care disappear. Develop protocols for moving babies around the hospital to ensure they are always accounted for.

Some may say that the government cannot afford to install such safety measures in a public hospital. Yet in the financial year 2016-17, the public hospitals returned billions of Ugandan shillings to the government treasury.

Rather than spending money on paying legal fees and damages for rights violations, I am urging the executive director of Mulago National Referral Hospital to invest in making systems that work for the people who use them. That means establishing policies at Mulago Hospital to respect the movement and safety of babies, dead or alive. The Uganda Nurses and Midwives council should hold its members to account when babies in their care vanish.

Every life in this country matters. We must ensure our public hospitals are doing all they can to protect our newborns.