On Wednesday, on behalf of the U.S. government, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office delivered a blistering attack on developing countries use of compulsory licenses for medical patents (Copy of U.S. statement available here.) This what we thought of the USPTO statement:

Open letter to those who collectively produced the May 23, 2012 statement to the WIPO SCP on the topics of patents and health

May 25, 2012

To each and everyone who worked on the SCP submission:

This letter outlines our concerns to the May 23, 2012 statement to the 18th Session of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Standing Committee on the Law of Patents (SCP), on the agenda for patents and health.

In its opening, the USPTO said the following:

“Some of the public health issues facing developing and least developed countries (DC/LDCs) include neglected diseases, the spread of TB, malaria and HIV/AIDS, and availability of medicines to treat these and other ailments. There is no easy solution to these problems. Reducing patent protection is not likely to solve these thorny issues. Furthermore, the notion that all developing countries face identical challenges and should apply the options that exist under international agreements in a single way – or that access to medicines would be enhanced by such an approach — has been rejected by many WIPO member states, including developing nations.”

Are you trying to say that reducing patent protection for AIDS drugs in developing countries did not enhance access to medicines? If so, where have you been the past 15 years? DHHS says the PEPFAR program pays on average 37 cents per day for ARV drugs to treat HIV/AIDS. Were you aware that by 2001, some 24 countries in Saharan Africa had granted patents on nevirapine and more than 30 had granted patents on 3TC, and that South Africa had patented d4T, and the brand name price for an ARV regime of these products was priced at more than $10k, in South Africa? Did you know that most patients in the PEPFAR program were using fixed dose combinations of these drugs, manufactured by generic drug manufacturers that benefited from compulsory licenses in South Africa and in many Subsharan Africa countries, including the LDC countries in Africa that used paragraph 7 of the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health to ignore patents on these products? Do you know how many people in Africa and other developing countries were receiving AIDS drugs in 2001 and how many are receiving AIDS drugs today?

Did you know that Mitch Daniels said, when serving as director of the Office of Budget and Management, that PEPFAR would not have been set up if the U.S. had to pay the brand name prices for patented AIDS drugs, and the possibility of using cheap India generic drugs made the PEPFAR program possible?

Is it your conclusion that Thailand did not expand access to patented medicines for AIDS, heart disease and cancer when it granted compulsory licenses on the patents for these products?

Is it true, in other words, that “reducing patent protection is not likely” to enhance access? Or is this a blatant falsehood, which the USPTO has expressed during the WIPO session on patents and health?

Is it true, as USPTO asserts, that:

“Weakening patent protection for innovative medicines is not a productive approach to improving availability of health care, because many other factors other than patents more directly affect the availability of medicines.”

In the case of HIV/AIDS drugs, is this true? Is this true for cancer drugs in the developing world? We mean, is it really “not a productive approach to improving availability” of care? And even if other factors are also important, as they surely are, is your point is that poor countries should ignore high prices, and focus all of their attention on solving every problem but high prices?

How much access to herceptin, the patented biologic drug for breast cancer, exists in developing counties? How many patients in India received access to Bayer’s version of the patented cancer drug Nexavar? Is it really, as USPTO claims, “not a productive approach” to override strong patent protection when cancer drugs are priced at $50k to $70k per year in a developing country? Do you have evidence that these drugs can be made accessible in developing countries at these high prices? Or, does the USPTO believe that people in developing countries do not need treatments for cancer, either because they somehow never develop cancer during their lifetimes, or their lives are not worth the cost of receiving the medicines?

We don’t want to be repetitive, but its hard not to when addressing repetitive assertions that strong patent rights do not present problems for access that are contained throughout the 1,200-word USPTO statement on patents and health.

We were surprised that the USPTO continues to raise the paucity of patented medicines on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, as evidence that patents do not harm access to medicines, because “their availability in many markets is still limited.” Yes, it is true. In countries where incomes are low, there are all sorts of problems, and not only a lack of access to essential drugs, but sometimes not enough food, or decent shelter, or education opportunities. But as indebted as we are to this brilliant insight, you of course leave out the more important insight, which is that the lack of patented drugs on the WHO list of essential medicines is not an accident, but rather a direct consequence of the impact of the patents on the prices for these medicines. Thus, as you know from our previous conversations and formal communications to WIPO on this topic, the most recent cancer drug on the WHO model list is an off-patent drug registered with the FDA in 1996. Does the USPTO appreciate or even care what it means when the global health authorities tell poor people that none of the cancer drugs developed since 1996 are “essential,” because they are too expensive to be cost effective when treating poor people? Is this what the Obama Administration endorses, a system of extremely unequal access to cancer drugs?

Does the USPTO believe that “Conducting a study on the positive impact of patent systems in providing lifesaving medicines to developing countries” is anything more that defending the indefensible, and using the power of the Obama Administration against the developing countries who have tried to fight the pharmaceutical company’s most egregious abuses in terms of pricing and anti-competitive practices?

As regards the USPTO objections to compulsory licenses, and your advice to developing countries to avoid their use, can you explain why the Obama Administration supported a mandatory compulsory licensing provision in the U.S. biologics pathway legislation passed as part of the health reform legislation, and if the Obama Administration expressed any opposition to these six compulsory licenses on medical technologies that were granted by courts in the United States?

2006: Voda v. Cordis Corporation

2007: Innogenetics, N.V. v. Abbott Labs

2009: Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v. W.L. Gore & Associates

2009: Medtronic Somafor Danek USA, Inc. v. Globus Med., Inc.

2010: Johnson & Johnson Vision Care, Inc., v. Ciba Vision Corp., 712 F. Supp. 2d 1285 (M.D. Florida 2010)

2011: Edwards Lifesciences AG and Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Plaintiffs, v. CoreValve, Inc. and, Medtronic CoreValve, LLC, Defendants. C.A. No. 08-91-GMS. United States District Court, D. Delaware., February 7, 2011.

Since the USPTO and apparently the rest of the Obama Administration is in complete denial of the harsh consequences tough IPR protections on medicines, allow me to point out that the George W. Bush Administration:

Embraced President Clinton’s executive order protecting the right of sub-Saharan Africa countries to grant compulsory licenses and use other TRIPS flexibilities to protect access to medicines (Executive Order 13155),

Negotiated the 2001 WTO Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health,

endorsed a new amendment to the TRIPS agreement to expand the ability to use compulsory licenses to export medicines,

Set a system for the FDA to approve the registration of generic medicines to treat AIDS that were produced under compulsory licenses,

Set up the PEPAR program and allowed it to become the world’s largest consumer of products manufactured under compulsory licenses,

Agreed, on May 10, 2007, to introduce public heath safeguards in the intellectual property chapters for developing country FTA agreements (a policy recently abandoned in the TPPA negotiation), and

Negotiated and agreed to the 2008 World Health Organization Global Strategy on Public Health, Innovation and Intellectual Property.

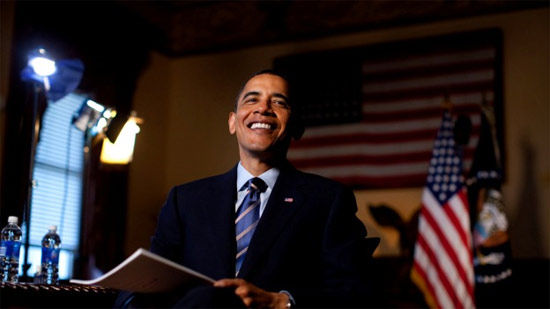

As pleased as we all are that Barack Obama is now president, the Administration seems to be leading a march backwards as regards policies for the poorest and most vulnerable people on earth. At WIPO this week, the USPTO is lending its considerable power and prestige to launch new attacks on the welfare of poor people in developing countries.

All governments are huge institutions, and the U.S. government is particularly large. Often decisions are made by groups of officials, each operating under somewhat different mandates and motivations. When there is a moral vacuum at the top, as is the case for the White House on matters concerning intellectual property and access to health care in developing countries, there is a risk that your own efforts will contribute to an outcome that you cannot in good conscience justify to your neighbors or families. Given the raw nature of corruption in the way that political campaigns are financed these days, it is not surprising that an agency like the USPTO has become an enemy of moral values and basic decency — abandoning even the more compassionate values embraced by conservative political figures like George W. Bush. But as individuals, you have to make some choices. When you fail to object to offensive statements such as the one delivered to the SCP on Wednesday, you become part of a large failure — the failure of ordinary people to recognize and resist the worst and most brutal acts by the powerful against the weak. You can do better.

Sincerely,

James Love, Knowledge Ecology International

Thiru Balasubramaniam, Knowledge Ecology International