– Compiled by Nakalembe Judith Suzan | CEHURD

In the heart of Northern Uganda’s Lango sub-region, Otuke District’s predominantly rural communities are grappling with severe challenges surrounding cultural practices, land inheritance, and access to justice. This is particularly true for women, elderly widows, and persons living with HIV (PLHIV), who face escalating violence and exclusion as their rights to inherit family property are systematically denied.

Despite Uganda’s Constitution and Succession Law guaranteeing equal inheritance rights, deeply entrenched cultural norms in Otuke continue to marginalize these vulnerable groups. Widows, especially those whose husbands died from HIV-related illnesses, are often unjustly accused of infecting their spouses, leading to eviction from their homes and denial of inheritance. Jannifer, a widow in Orum Subcounty, recounts, “When my husband died of HIV, they said I was the one who killed him and threw me out of our home,” highlighting the cruel intersection of stigma and property rights violations.

Women who have only daughters face similar injustices. Once their daughters are married, these women and their children are frequently disinherited. Juliet from Agwete Subcounty, forced off her land by a brother who claimed sole ownership, laments, “They tell us we no longer belong here,” emphasizing the systemic denial of property rights.

Elderly widows suffer additional brutality. Grandsons often resort to violence, including rape and arson, to seize control of property, while childless elderly women are accused of witchcraft to justify their eviction. These inheritance violations targeting especially women, girls and persons living with HIV, stand in stark contrast to Uganda’s legal protections, which affirm that all children, regardless of gender, and widows are entitled to inheritance.

The failure to enforce these laws has intensified the plight of women and PLHIV in Otuke District, perpetuating a cycle of marginalization and injustice. Access to justice is further complicated by the district’s limited judicial infrastructure. Otuke has only a Grade One Magistrate’s Court, which presents significant jurisdictions barriers for victims seeking legal redress

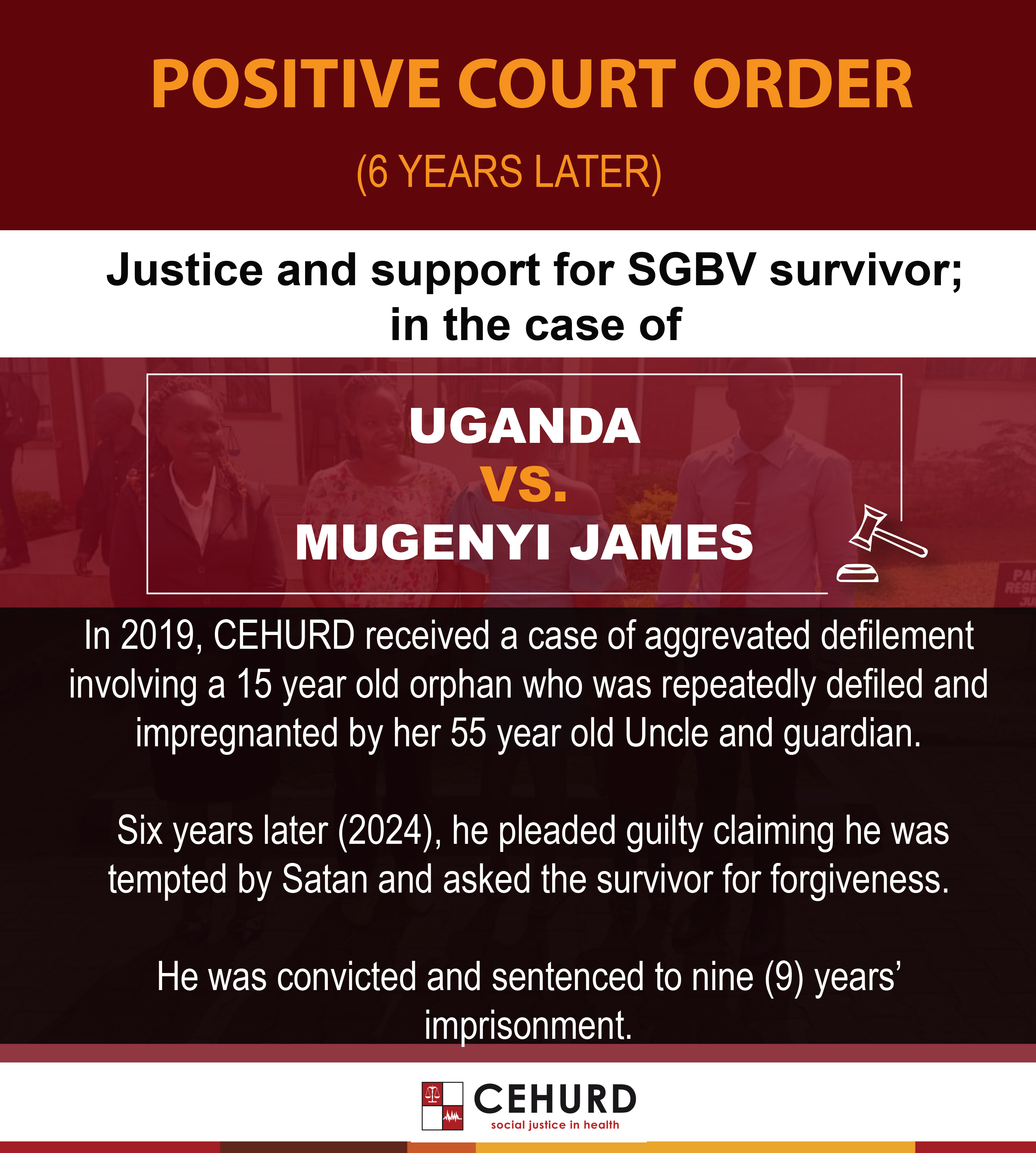

CEHURD, supported by TASO and the Global Fund, is spearheading efforts to combat these injustices. By implementing robust legal education programs, raising community awareness, providing free legal aid, and advocating for effective law enforcement, CEHURD is challenging harmful cultural practices and striving to bridge gaps in legal protections. They are also addressing the challenge of court accessibility, helping victims navigate the complex legal system and overcome barriers to justice.

These initiatives are crucial in empowering vulnerable groups to claim their rights and promote a more just and equitable society. However, without enhanced enforcement of existing laws and improved access to judicial services, women, girls, and PLHIV in Otuke District will continue to face severe discrimination and injustice, remaining at the mercy of discriminatory cultural practices that deny them their rightful place in society.

Compiled by Nakalembe Judith Suzan, Center for Health, Human Rights, and Development, Community Empowerment Programme.